Pvt. David Drake Blue

1818 - 1896

David Drake Blue* was born in Kentucky in the year 1818. Born into a long history of enslaved families in the South, we cannot be certain who his parents or family were, nor their origins. For the entirety of his life, David Drake Blue answered “unknown” when asked for the birthplace of his mother and father on census records. Since enslaved persons were legally considered to be the property of their enslavers, detailed name and familial records were not kept. In these cases, all research must come back to the paper trail, in an attempt to recover the history and humanity of those who were not granted basic human rights at birth. This is how we trace an outline of David Drake Blue’s life.

David Drake Blue is recorded on census records throughout his life as “Mulatto,” meaning he was possibly the mixed-race child of an enslaved woman and her white enslaver. He was given the name David and the surname of his enslaver, Miles C. Drake, a wealthy landowner and farmer born in Kentucky in 1808 who likely inherited David along with his father’s enslaved, and property, upon Jacob Drake’s death in Kentucky in 1839.

The day is October 12, 1850 in Mason County, Kentucky. A man, who we can safely assume is David Drake Blue, is listed on the 1850 Slave Schedule belonging to Miles C. Drake. This 33 year old man is listed among five enslaved persons, recorded as Male, Mulatto, and a freedom seeker, meaning he has previously attempted to escape. Below his record there is a 15 year Black old female, also enslaved by Miles C. Drake, who shares the same birthdate and complexion as David’s future wife, Eliza. It is likely David and Eliza meet and commit themselves to each other while enslaved on the Drake plantation, although not legally allowed to marry. Five years later in 1855, while still held there, David and Eliza have their first child, Belle. Even though David Drake Blue’s first daughter is born into slavery, his will to be a freeman never escapes him.

Two years later, in 1857, Eliza gives birth to their second daughter, Maria. By 1860, David, Eliza, Belle, and Maria are moved, along with Miles C. Drake’s other enslaved and his entire family estate, to Liberty, Missouri in Clay County. Though we don’t know the particulars of the move, records show that between 1820 to 1860 there is a large migration of slaveholding families from Kentucky to Missouri, Tennessee, and Texas. The bluegrass state has gradually become overworked and farmers look for more fertile, undeveloped lands to use for cultivating their hemp and tobacco crops. Since Miles C. Drake is a farmer with a large estate, it’s likely this need for bountiful land is a primary factor in the migration.

In 1860 David and Eliza welcome their third daughter, Fannie, into the world in Liberty, Missouri. The family continues to live and labor without their freedom on the M.C. Drake farm. In 1860 Abraham Lincoln is elected president, although not one vote was cast for him in Clay County. One year later, because of uncompromising differences between free and slave states over the power of the government to prohibit slavery in territories that have not yet become states, the Civil War breaks out. As David Drake Blue and his family continue to grow and labor for M.C. Drake, local loyalties divide between the Union Army and the rebel Confederates of Liberty, lead by many slaveholding men. In a battle at Blue Mills Landing on September 17, 1861, the Union loses 126 men. Liberty’s William Jewell College is set up as a hospital for the injured and the dead are buried onsite at Mt. Memorial Cemetery. The following year, Eliza gives birth to twins, their parent’s namesake, Elizabeth and David.

The year is 1863 and the country is in the middle of a brutal civil war. Enslaved laborers work the hemp and tobacco fields of Clay county through another muggy Midwestern Summer. A notice hangs nailed to a post in the center of small towns all across the South and slaveholding Midwest.

“TO COLORED MEN! FREEDOM, Protection, Pay, and a Call to Military Duty!” For men like David Drake, these words have never coexisted before. The idea of earning freedom from the very country that founded his enslavement has been no more than a dream. Until that moment, if you are enslaved, you are denied rights of citizenship, unpaid for your labors (except in very rare cases), and the only protection you can hope for is directly linked to your monetary worth as a piece of chattel property. If you are enslaved with your family members, it is likely that eventually one or many of you will be sold and separated. In Liberty, enslaved persons are bought and sold regularly at public auction on the corner next to the Clay County courthouse for sums of $500 to $1500 per person ($16,000 to $32,000 in today’s currency). Such sales are recorded and reported by the Liberty Tribune, sometimes even next to ads selling livestock.

It is possible that David Drake saw a freedom poster himself while still enslaved by Miles C. Drake, although it was illegal for enslaved persons to learn how to read or write and we see on census records that David Drake Blue reports to census secretary, “Can’t read / Can’t right.” Maybe he heard echoes of the famous words of Frederick Douglass from fellow enslaved persons, "Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship."

January 1, 1864, a new year and the Civil War continues. Miles C. Drake fills out paperwork enlisting David Drake Blue in the Union army. The paperwork guarantees Miles C. Drake will get financial compensation for David Drake Blue’s service, as “the lawful owner of David Drake” as was common custom at the time for many slaveholders. In the collection of enlistment papers we see the first detailed physical description of David Drake Blue, “Five feet three inches high, Brown complexion, Dark eyes, and Dark hair.” David Drake Blue continues to serve and fight in the Union Army for the next 19 months.

January 20, 1865 an announcement runs in the paper: “Be it ordained by the people of the State of Missouri, in Convention assembled, That hereafter in this State, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitute, except in punishment of crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, and all persons held to service or labor as slaves are hereby declared free.”

Hundreds of miles away from home, David Drake Blue continues to serve as a soldier in the Union army until August 23, 1865, when he is discharged due to illness. On his Certificate of Disability for Discharge we also see the medical examiner records a missing index finger on David Drake Blue’s left hand, “Loss of left index finger which occurred before enlistment.” Slave Narratives published in the Library of Congress record several instances of enslaved persons, who attempted to escape plantations, being punished by amputation of a finger on their non-dominant hand. We can never be certain but this may have been the case for David Drake Blue.

All told, he spends over a year and a half away from his wife and five children, bravely serving in the army for the country that has, up to that point, recognized him and his family members, as 3/5ths a person. On his discharge paperwork his commanding officer records, “He has always been a good and faithful soldier.”

The war ends and Miles C. Drake can no longer hold David Drake Blue or his family. Following their freedom, David and Eliza Drake Blue continue building the family they started while enslaved. In 1866 their Daughter Anna is born, followed by the birth of their daughter Louisa in 1868..

In 1870, at age 54, David Drake Blue has changed his surname, now going by David Blue. Many enslaved persons changed their names after emancipation, believing that the names they were given at birth were “slave names,” not reflective of their full humanity. David and Eliza live in Liberty in their own dwelling for the first time, along with their children Maria, Fannie, Elizabeth, Anna, Louisa, and David and Austin Walker, an 82 year old Black man (his connection to the family is unclear). David Drake Blue works as a farm hand while Eliza keeps house and takes care of the children. That same year, the 15th Amendment ratifies the vote, making it possible for Black men to vote for the first time. In Clay County, also known as “Little Dixie,” poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and bullying from the public likely kept most Black men from being able to cast a ballot. Three years after the ratification of the 15th amendment, Eliza gives birth to their last child, their son Robert.

In the summer of 1880 David Drake and his wife Eliza are living in East Liberty Township with their son-in-law William Gillespie, their daughter Fannie, and granddaughter Mattie, who is two years old at the time. William is a house carpenter in the now historic district of Liberty, possibly even working on some of the dwellings that now stand with markers as century homes. Fannie keeps house, Eliza is hired out from home for work, David Drake works as a laborer, and their daughter and son Louisa (12, attending school) and Robert (7) also live with them. It should be noted that, in a 1900 census, Eliza Drake Blue will report that she has given birth to 13 children, and that 8 children are living. Though we cannot know the details, infant mortality rates among enslaved were much higher than among whites. Whatever the causes of death we can be certain that, for David Drake Blue and Eliza, the grief that accompanied the loss was real.

The day is 26th of November, 1896 in Liberty, Missouri. At age 75 David Drake Blue breathes his last. He is buried by his family in an unmarked grave in the segregated section of Fairview Cemetery. Although his service to his country has gone unrecognized in Fairview until now, we honor the memory of his life, his good and faithful service to this country, and his will to free himself and his family. We remember his striving for freedom, his longing to work hard in forming a life, legacy, and name of his own.

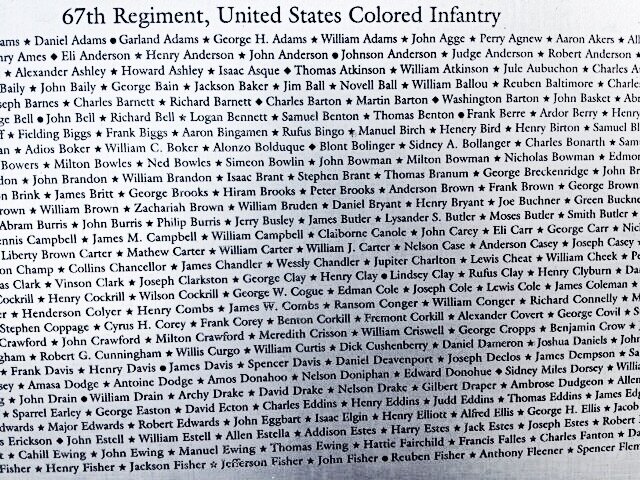

Today, David Drake Blue’s name can be found, under his enlisted name of David Drake, at the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington D.C., carved into the granite, along with the names of his fellow soldiers of the 67th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry.

Article Sources:

* David Drake later changed his name to David Blue, so for the purposes of honoring his self-given name while also keeping record of the paper trail, he is herein referred to as David Drake Blue.

Image Credits:

Come and Join Us Brothers. U.S. Colored Troop Recruitment broadside. 1863-1865. Courtesy of Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library at Duke University

Am I not a Man and A Brother? Image published in 1837 by the American Anti-Slavery Society on the broadside of an abolitionist poem. The woodcut features an enslaved man down on one knee holding up his chained wrists. This image—or variations on it—was used by antislavery societies in both the United States and in England. The caption beneath asks, “Am I not a man and a brother?” Courtesy of the Library of Congress

1850 Slave Schedule The National Archive in Washington DC; Washington, DC; NARA Microform Publication: M432; Title: Seventh Census Of The United States, 1850; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29

General map of the United States, showing the area and extent of the free and slaveholding states, and the territories of the Union, by Henry D. Rogers (1857). Available through the Library of Congress.

Call to Colored Troops available through the National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/files/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war

Advertisement placed in Liberty Tribune.

Enlistment & Civil War papers via Fold3 Military Records.

Census Records made available through Ancestry.com.